By Nicole Etchart and Loïc Comolli, NESsT Co-CEOs

An estimated 800 million people will need access to decent work in the next five years.[1],[2]Social enterprises throughout the world present an opportunity to meet this need.

They use innovative business models that connect vulnerable groups to formal labor market jobs; these models range from workforce development and job placement to direct employment. Despite the importance of this work, the majority of these enterprises are only measuring outputs such as number of jobs, and not the quality of these jobs and whether they are truly “decent” and moving these groups out of poverty and toward a path of social mobility.

The reasons for this are many. Qualitative measurement is costly and complex. There are few widely accepted indicators or practices, making many in the sector believe that efforts to date are quite subjective. However, despite these challenges, the growing interest and support for social enterprise across the globe calls on us to begin to make an effort to measure their qualitative impact. Doing something, even if small and somewhat imperfect, is better than doing nothing at all.

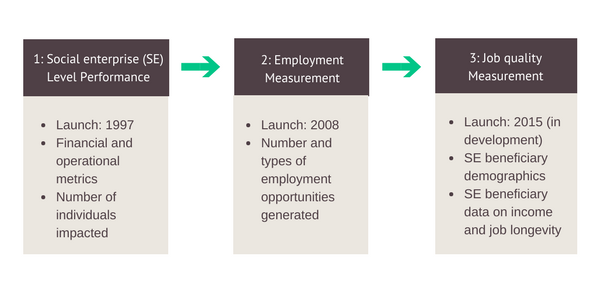

This is why in 2015, NESsT decided to begin measuring the quality of the jobs and contracts generated by its portfolio of enterprises. Measuring impact was not new for NESsT. Since its founding in 1997, we have been measuring the performance and impact of our portfolio. Our performance measurement has evolved through three phases; each one augmenting the scope and types of indicators collected.

The current set of indicators (from Phases 1 through 3) includes 36 metrics collecting data at the social enterprise and beneficiary levels. These indicators framed our definition of ‘decent work.’ See Table 1 for the list of indicators.

NESsT launched Phase 3 focusing on job quality measurement, in response to its new strategy to exclusively support social enterprises that provide employment and income to those most in need.

Were these jobs moving these communities out of poverty by providing them with a secure and livable wage?

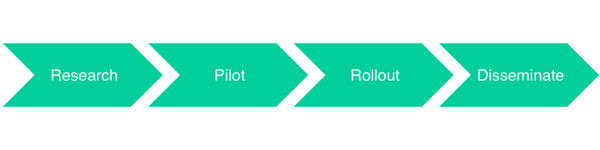

Although we had some indications that this was happening among the beneficiaries of our portfolio, given the lack of both financial and human resources, we had not measured it in a systematic way. It was now necessary to collect job quality metrics to validate these beliefs and to do so we put the following process into place:

Research existing employment measurement models to understand their objectives and applications

NESsT reviewed existing measurement systems from international organizations (e.g., ILO) measuring employment quality to understand their applicability for social enterprises. Furthermore, the research surveyed 25 emerging market countries to collect employment metrics and use as benchmarks for jobs created by social enterprises. These metrics include minimum and average wage, poverty rates, job longevity and job security, and employment subsidies. The research also analyzed employment barriers for the following target groups: at-risk youth, ethnic minorities, women, people with disabilities, immigrants and the elderly.

Pilot job quality definitions and metrics on a sample of social enterprise beneficiaries

We consulted a cohort of social enterprises and their beneficiaries to define the concept of job dignity. These enterprises include employment, placement and supplier business models. The results led to seven key concepts that social enterprises and their beneficiaries consider important for dignified employment, including (a) adequate earnings, (b) decent hours, (c) stability of work, (d) work-life balance, (e) fair treatment, (f) safe work environment, and (g) social protection.

We decided to measure primarily on the first three concepts, and added demographics concepts to capture the profile of social enterprise beneficiaries. The research then grouped job dignity and demographic concepts into three categories and 16 indicators (see Table 2 below).

Table 2: Dignity Indicators

Although we recognized the importance of understanding work-life balance, fair treatment, safe work environment, and social protection, we decided to keep the survey simple, and not overwhelm beneficiaries with too many indicators. We hope to add these dimensions the future.

NESsT collected these metrics on a sample of 50 vulnerable individuals employed by our portfolio enterprises. The main findings of the pilot include:

- 46% of beneficiaries stopped their education at high school

- Beneficiaries worked 36 weeks of the year for the social enterprise

- Majority of beneficiaries have worked for the social enterprise for less than one year

- Beneficiaries were optimistic about the operations of the enterprise, but they were concerned about their job stability

- Beneficiaries received wages above the minimum wage for their countries

- Share of social enterprise income to total household income is much higher for employees than suppliers

We identified and addressed a number of challenges to streamline the metrics and data collection process during the rollout phase. These included:

Table 3: Dignified Employment Pilot Challenges

Challenge

Solution Implemented

Working with external consultant versus in-house staff to collect data

NESsT validated the survey methodology and tools with external researchers and ecosystem actors before starting the pilot. Data collection was conducted by NESsT Portfolio staff – persons that are working closely with social enterprise managers but not with beneficiaries who were subject of the survey. Interviewers were very well trained and prepared to do the survey to mitigate the risk of data distortion.

Income data are a delicate topic, need to build trust during the survey

Face-to-face interviews were much more efficient than phone interviews – beneficiaries had the opportunity to ask questions and to understand objectives of the research. It helped to build trust and relationships with the interviewee.

Geography and weather conditions

In Peru and Brazil, it was difficult to interview members of remote communities. In some cases NESsT asked social enterprises to conduct interviews since they are closer to the beneficiaries. Furthermore, NESsT plans to collect data taking into account weather conditions: e.g., end of the year in Peru due to the rainy season and March/April in Central Europe to avoid travelling during the winter.

Resources – time, money, staff

Data collection is time and money consuming and NESsT is looking for more efficient ways of conducting this process. We are researching different technologies including mobile apps to reduce costs. During the pilot we conducted interviews to coincide with portfolio site visits to save money and time for our staff.

Educational and social background of beneficiaries

Some beneficiaries have difficulties understanding survey questions, to calculate income, and even to communicate with interviewers. Direct face-to-face contact with interviewee helps to communicate efficiently. In some cases tutors or social enterprise staff assisted during the interviews or confirmed the validity of the data (e.g., in the case of people with mental health problems).

Language

We had to translate the questionnaire into five languages and keep it consistent. We adjusted the questionnaire to the realities of five countries through internal trainings.

Sampling size and representativeness

Due to limited resources, we need to keep sample size at a reasonable and feasible level, while keeping it representative and inclusive (all countries, all marginalized groups, all business models). NESsT decided to survey 100% of social enterprises in the portfolio, and around 10% of the beneficiary population. We will use quota-sampling, which is representative.

Benchmark data

It was challenging to find reliable benchmark data for all countries and all types of business models, including the industries in which they operate. While in Central Europe statistical data is current and available, in Latin America it is more challenging to obtain. For these reasons we limited benchmark data to a few, easily- available variables including: minimum and average wages, poverty line, purchase power parity.

Cultural and legal differences

Many country differences exist in terms of labor laws and social protection. To address this issue, we limited the number of indicators to income level and job longevity. These two indicators allow us to compare results among countries and to aggregate data at the portfolio level.

Methodology does not measure impact in terms of long-term psychological change of beneficiaries

NESsT does not have the capacity to conduct such research and to track this dimension of impact. We might consider this in the future, as an additional survey conducted less often than annually (every 3-5 years).

Methodology was sometimes too complex

Based on the feedback from interviewers, we re-designed the methodology after the pilot, reduced number of questions, removed data that was not relevant for us and made an e-version to simplify the process of gathering and aggregating data. Now the questionnaire has 17 questions and takes approximately 10-12 minutes to complete.

During the pilot phase NESsT also upgraded its current Customer Relationship Management (CRM) system to manage and analyze the new job quality metrics. We worked with an outside vendor to customize our CRM platform for the new metrics.

In late 2016 and early 2017, NESsT rolled out its employment survey in order to begin capturing baseline. Data was collected on demographics, income and job longevity through a questionnaire tested and validated during the pilot.

We collected data from 16 enterprises in our portfolio (out of 28) and a sample of 10% of their beneficiaries. The sample represents approximately 350 individuals and included supplier models, employment models and placement models.

No doubt that this was not an easy process. In addition to having to plan around the effects of El Niño in Peru and the long distances needed to reach beneficiaries living in remote communities, capturing the data from the beneficiaries themselves was also challenging.

A key goal of the survey was not only to understand individual income- from both suppliers and direct employment/placement models- but how it compared to overall household income. Often interviewees did not have this information and did not know how to obtain it. We used a series of proxy questions to derive the information.

In relation to job longevity and security, we asked interviewees if they had a contract, and if so, we asked its duration. But since some do not, it was also important to know if they thought they would have this job the following year. The results of this were quite positive, with 80% having a contract that they expected would be renewed and 85% believing that they will still have their jobs next year.

By sifting through the data to benchmark against minimum wage and poverty level, we are beginning to capture a very clear picture of our portfolio and their beneficiaries. On the plus side, we see that beneficiaries are earning between 56-256% of minimum wage in their countries. Once we are able to compare income earned in 2016 to that earned in 2017, we will begin to understand how income improves in correlation to enterprise performance.

On the delta side, we are concerned that the data shows that some of our supplier models are contributing a smaller percent of household income than we had expected, and we want to understand why; although we were pleased to see that overall household income ranges from 98-580% of the poverty line, depending on the country.

By creating this baseline, we can set precise goals and indicators with our portfolio on where beneficiaries should be a year from now.

This in turn will help our portfolio companies make more informed decisions related to their businesses and weigh the trade-offs between reaching more people versus providing their current employers and/or suppliers with better quality jobs and contracts.

It’s critical that we analyze the outcomes of these efforts and similar ones with our colleagues so that we can learn from each other and begin to benchmark the sector overall. Ultimately, this data will be shared in the form of dynamic data and storytelling with the social enterprise sector, and other intermediaries -- investors, accelerators, incubators, -- that are supporting social enterprises.

We are excited to have taken these concrete and pioneering steps to measure the dignity aspects of the jobs generated by our portfolio. The process is by no means perfect. In particular, we need to explore lean data technologies that lower the costs and time for data collection, as well as improve analysis and reporting.

However, these initial efforts have been eye opening. By adding dignity dimensions to the numbers, we can really begin to make qualitative impacts on the lives of those most in need. As one of our colleagues said:

“Even if individual incomes are still small, they can be meaningful at the family level or for a single mother. When conducting the surveys, we encountered cases where two people live on a 400 lei salary. 1000 lei extra per year is a significant amount, representing an increase in annual revenue of 20%."

By deepening our measurement, we are hearing directly from the people we exist to serve.

Table 1: NESsT Flagship Indicators